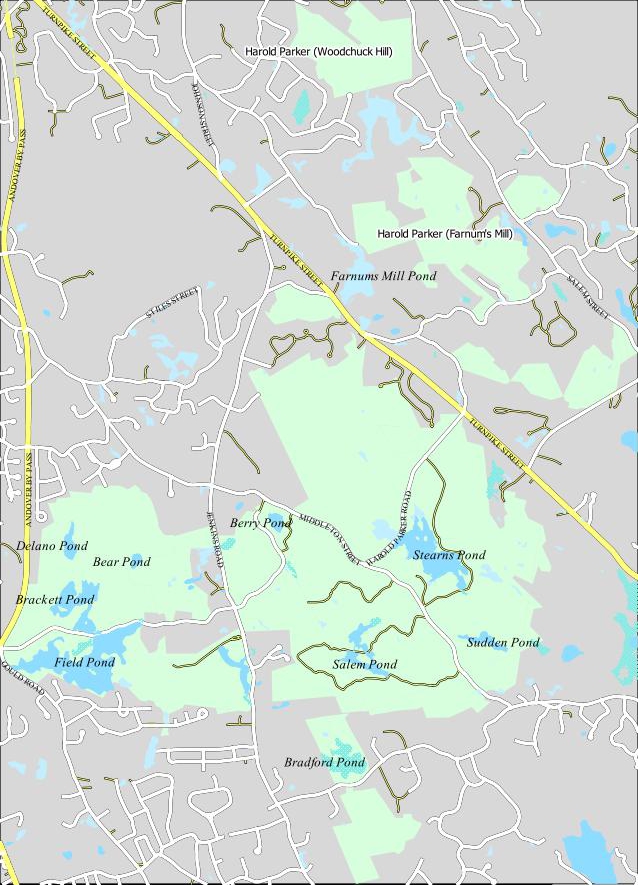

The majority of the park lies 20 miles north of Boston within the boundaries of Andover and North Andover with smaller portions inside the boundaries of North Reading and Middleton.

Several parcels of land that make up Harold Parker are disconnected from the main portion of the park. The largest of these are the Woodchuck Hill Parcel (approximately 165 acres) and the Farnums Mill Parcel (approximately 265 acres). Both lie Northeast of the main park and have small trail systems.

According to the 2013 DCR Management Plan, the park includes 56 miles of trails, 9 artificial ponds and 2 natural ponds (Bear and Berry Pond are natural kettle ponds). Approximately 18% of the park (601.5 acres) consists of these ponds and associated wetlands.

The Skug River flows from North to South through the western half of the park, entering near Salem St. through the adjacent Skug River Reservation and exiting south of Harold Parker Road to eventually flow into Martin’s Pond outside the park.

The lowest elevation of the park is 78ft above sea level in between Field Pond and Lorraine Campground. The highest elevation of the park is 333ft above mean sea level in the Woodchuck Hill parcel.

History

Pre-Historic Use and Settlement

Native Americans were present in New England for over 10,000 years and Harold Parker State Forest for at least 7,000 years prior to the European’s arrival but there is comparatively little knowledge of the people and cultures that existed in the region. 1 No written record exists from the Native American perspective and so archaeology is the main source of information.

There is an abundance of archaeological sites located in Andover, most of which are located along stream and riverbanks. The Skug river flowing through Harold Parker is small relative to the nearby Merrimack, Shawsheen and Ipswich but multiple sites have been found along its banks. 2

One of the earliest sites along the Skug is a stone workshop used between 7,000 and 2,000 years ago. Here, early Native Americans chipped blanks of soapstone from boulders to hollow into bowls. 3 This site was likely abandoned as ceramics technology replaced soapstone around 2,700 years ago.4

A second site, just outside the park and from a similar time period, lies further south where the Skug River enters Martin’s Pond. This site is believed to have been a dugout canoe workshop. It’s thought that the builder would use fire to weaken a portion of a log, then chip out the ash and charcoal using stone tools to complete the canoe.5

A human burial, dated to between 5,000 to 350 years ago, was found within the park on the former grounds of Jenkins farm. Several stone implements were found nearby, including fragments of two Bannerstones, which are highly polished and decorative weights used to improve the performance of a hunting spear. 6,7

In all, six different pre-historic sites were found in or near the park.8

The Skug River itself is thought by some to have a Native American Algonquin name. Translations include “Snake River” and “Black River”.9,10 Occasionally the name is said to be a misspelling of “Skunk” but the source was a historian’s casual observation that the words sounded similar. 11

Contact Period

The information regarding names, groupings and affiliations of the Native Americans inhabiting colonial-era Andover are confusing and often contradictory. This is largely due to an incomplete and unclear historical record. In addition, historians often mistook place names such as “Agawam” and “Naumkeag” with tribe names, while misinterpreting and intermingling family affiliations, tribes and tribal confederations.12,13

At the time of European contact, it is thought that the Massachusett confederacy occupied coastal Northeastern Massachusetts and the Western Abenaki occupied the interior. The exact boundary between their territories ia unknown and so the Native Americans of Harold Parker may have been affiliated with either group. It has been proposed by some researchers that the territorial boundaries are loosely aligned with river watersheds. If this holds true, Harold Parker being in the Ipswich River watershed would place it in Massachusett territory, although these boundaries may already have begun to break down by 1600.14

Between 1616 and 1659 the Native Americans of northeastern Massachusetts suffered multiple epidemics of various European diseases including smallpox, influenza and diphtheria. The Native American populations suffered more than ninety-percent casualties of their entire populations. It is estimated that by the mid-1600s, less the 300 adult Native American men remained in the Merrimack Valley. 15

By the time of Andover’s settlement around 1646, it is unlikely that many Native American people remained in or near Harold Parker State Forest. There are only a handful of historical accounts of Native Americans in Andover and none relate to the park.

Wolves, Wilderness and Woodlots

The park history is closely intertwined with the history of Andover and North Andover. Until 1855 the two were a single town named Andover. 16 Andover was incorporated in 1646 with almost 60 square miles of land. 17,18

Following English tradition, the houses were located in a compact village center in what is now North Andover. In addition to their ‘house lot’, each family was given initial grants of land located throughout the rest of the town for farming. During the next two decades the town made several more major ‘divisions’ of town land between the families. By the last division of 1662 only 12 of the original 60 square miles had been allotted to the families. The remaining land was held as ‘Common land’ for the use of the townspeople. 19,20

The Osgood family was given 400 acres during this last division. 21 They would eventually use this grant to claim a tract of land which is now part of Harold Parker State Forest. 22 (See the following section on Peter Osgood’s Farm). It was common for families to wait several decades before claiming their grant. 23 The Osgood family didn’t claim their land at Harold Parker until sometime after 1695. 24 Until then, most or all of Harold Parker was part of Andover’s ‘Common land’.

The earliest town records tell us that each family was to “..have liberty and privilege of the common for feeding cattle and use of wood and timber..”. The selectmen restricted the use of the common and laws were in place to prevent the townspeople from erecting fencing or removing timber outside the town. Occasionally, small portions were leased for temporary farming, to be returned to common use at the end of a set term. 25

Of some note is that these same town records refer to wolves several times. Wolves most certainly existed in Harold Parker State Forest throughout the 1600s and before. The majority of entries relate to the bounties offered for killing wolves, the last entry being in 1701. 26

Peter Osgood’s Farm

Peter Osgood was born in Andover in 1663. He was the grandson of John Osgood (1595-1651) who came to New England in 1638 and was among the first ten families to settle Andover in 1645. Peter’s father, John Osgood Jr. (1630-1693), was a prominent leader in the town and his mother Mary Clements Osgood (1637-1710) was one of several people from Andover indicted and imprisoned in Salem for Witchcraft.27

In 1662, the town gave Peter’s father a land grant of 400 acres. When John Osgood Jr. died in 1693 he left this grant to Peter and his brothers28. Sometime between 1695 and 1710 the brothers used the grant to claim a piece of land in the Southern part of Andover which was surrounded by ‘common land’. Peter had since moved to Salem, becoming a Deacon and a Tanner. He bought out his brothers shares of the land in 1710 and 1711.29,30,31. In 1745, Peter sold the Northwest corner of “Osgood’s Farm” to Samuel Jenkins32. He died in 1753 and the next year his wife Martha began to sell other pieces of his Andover farm to pay his debts and funeral costs33.

By the time of its sale the farm was over 500 acres in size and included at least three houses. While we can’t be sure of the exact boundaries, the Northern property line crossed Berry Pond and the Southern property line ran along the present day North Reading town line, covering much of the central part of Harold Parker State Forest. The deeds describing these land transactions include references to Salem Road and what is now Jenkins Road, along with Osgood’s Hill which is covered in more detail below34,35,36,37,38,39. In the probate papers settling Peter’s estate, the farm is described as tillage (cropland) and pasture.40

One small mystery of Osgood’s farm is that Peter’s brother Samuel tells us in the 1710 deed that the farm is sometimes called ‘gibbet plaine’.41 A ‘gibbet’ was a post with hanging chains and shackles used to both execute criminals and display their remains as a warning.42 There is no record of any execution ever taking place at Andover and such an occurrence would have been unlikely as executions in colonial Massachusetts, with the exception of the Salem witch trials, took place at the Essex County Court (Ipswich) or the Massachusetts Bay Court (Boston).43

Osgood’s Hill

Not to be confused with the better known ‘Osgood Hill’ on the Stevens Estate in North Andover, ‘Osgood’s Hill’ lies in Harold Parker State Forest and can be reached using the loop trail running between trail markers NA9 and NA10.

In 1709 the town of Andover, while remaining a single town, split into a North and South parish with separate churches. A committee was appointed to lay out the dividing line which began at the Merrimack River in the North and ended at “…a white oak tree marked A and R, being a bound tree between said town of Andover and Reading, with stones about it, standing on a hill known as Osgood’s Hill.”44

In 1904 a Massachusetts State law was enacted to define the boundary between North Reading and Andover:

“The following described line shall hereafter be the boundary line between the towns of North Reading and Andover : — Beginning at the present corner of the towns of Andover, North Andover and North Reading, at a granite monument lettered A—R, standing on the summit of Osgood’s Hill in latitude forty-two degrees, thirty-six minutes, fifteen and eleven hundredths seconds and longitude seventy-one degrees, four minutes, thirty-six seconds…”.45

Osgood’s Hill is mentioned in both descriptions with the geographic coordinates given in the state law. The granite monument still stands at this point on the top of the hill just off the trail as seen in the photo below.

Carlton’s Path through Falls Woods

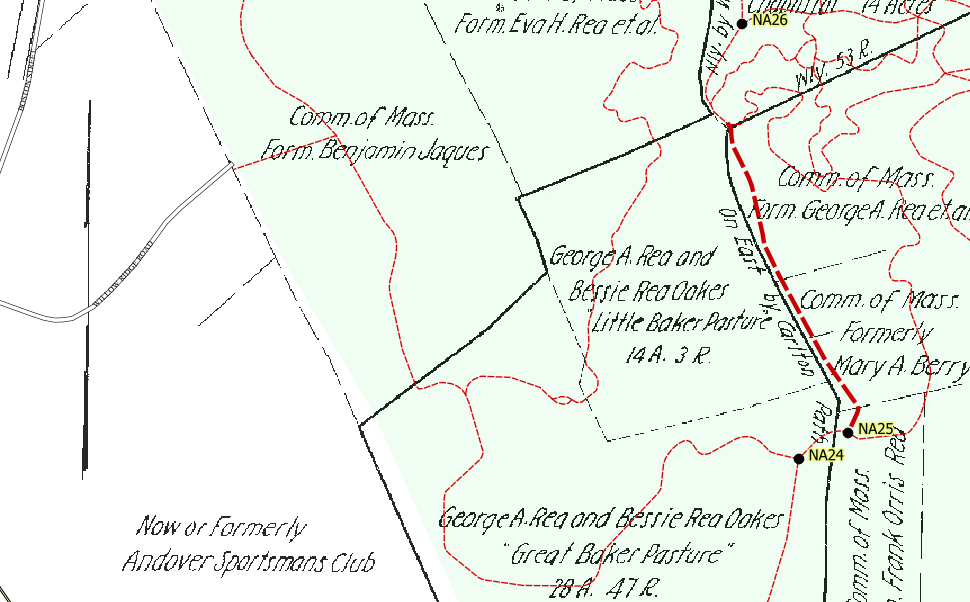

A segment of trail that runs Northwest from trail marker NA25 has been in continuous use for at least the past 300 years.

On occasion, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts prepared land plans of property it intended to purchase for Harold Parker State Forest. A portion of one of these land plans from 1954 is pictured below with “Carlton’s Path” labeled on the original plan and the present day trail system overlain on the map. The section of trail that was once “Carlton’s Path” is indicated by the thick dashed red line.46

A number of old deeds traced to Harold Parker State forest mention this path. One of the earliest from 1729 describes it as John Carlton’s Path.47 We know little of John Carlton other than that he was a Cooper (maker of casks and barrels).48 Another from 1746 describes this as the path used by Abraham Foster to cart his hay in from Falls Meadow.49 Many of these same documents describe the path as running through Falls Woods.50

Falls Woods is mentioned in twenty or so of the deeds selling land to the State, along with many of the historic deeds that can be traced to the park. The woods are variously described as Falls Woods, Falls Meadow and Falls Meadow Woods.51 In the oldest documents from the 1700s the names of ‘Fawls Woods’ and ‘Fowls Woods’ appear.5246 These woods were extensive and seem to apply to the entire Eastern portion of the park from Salem St/Middleton Rd, East to the Middleton Town line.

The origin of the name is unclear. One local historian theorized that it may be a family name. She suggested that a wealthy Boston merchant by the name of Thomas Fowles may have owned these woods at one time but admits having no evidence to support the idea.5344

The First Houses

By the early 1700s, land was in short supply and settlement began to spread to the southern part of Andover near the current park boundaries. Several houses from this time still stand on lots adjoining the park. Some of these may have been erected during the time of Peter Osgood’s Farm. According to the Andover Preservation Commission website, 53 Harold Parker Road was constructed between 1720 to 1776, 140 Jenkins Road (demolished in the 1970s) was constructed between 1730 and 1780, 8 Douglas Lane (Jenkins Farm) was constructed at or before 1758 and 52 Harold Parker Road was constructed in 1765. Today these houses stand on small lots surrounded by subdivisons and parkland but originally they would have consisted of much larger parcels to support pastures, farming and woodlots.

Sawmills

Prior to the twentieth century, at least three water-powered sawmills were built within the bounds of Harold Parker State Forest. The remains of two of these mills are extant and can be visited, while the remains of the third were demolished during the construction of the Brackett Pond dam in the 1930s. All three mills were in close proximity making it difficult to disentangle their histories and identify each individually in the historical record.

Holt’s Sawmill

In 1685, the Town of Andover gave Henry Holt land and the right to operate a Saw Mill, provided that he did not sell any of the lumber outside of town54. We don’t know the exact year the mill was constructed but Holt would’ve been the earliest resident to construct a Saw Mill in the area. The exact location of this mill is uncertain but it appears to be within the bounds of the park55,56,57. The Jenkins family may have built one of the later mills on top of this site.

Jenkins’ Sawmills

The Historic Jenkins Mill Site appears just north of trail intersection A10 on the State Trail map. Two parallel stone structures which may have been portions of the spillway and tail race of the mill can be seen not far from the trail. At the time of his death in 1878, William Jenkins leaves this saw-mill to his widow Polly. He also mentions that the mill is built upon land sold to him by Eben Jones and Samuel Abbott58. While the land that Jones sold to Jenkins can be traced back to the Holt family, neither of the early deeds reference a saw mill or water privilege, indicating that William and his family may have built (or re-built) this mill themselves59. A wooden mill and mill building stood at the site until a fire in 189360.

One local historian (Bessie Goldsmith) tells us that Frank Jenkins described to her “hauling ships knees with ten pair of oxen and a horse to Middleton on their way to Danversport”.

Another mill was owned and operated by the Jenkins family starting with Benjamin Jenkins in 179961 but the mill is older and passed through several other owners.

At some point in the early-to-mid 1700s a man named Timothy Fuller Sr. of Middleton was in possession of this mill62. Timothy Fuller’s son (also named Timothy) sold the mill to Benjamin Upton of Reading in 179963. Upton owned the mill for exactly three days before selling it to Benjamin Jenkins for a profit of thirty-two dollars64. Benjamin Jenkins sold it to his son William in 182965.

There is some bitter irony in that an early owner, Fuller, held some number of African-Americans in slavery66,67, while its final owner, William Jenkins, was known for his anti-slavery activity68,69,70. It is not clear which of the three mills was sold to Jenkins by way of Fuller and Upton. It may have been the mill eventually sold to Henry J. Gray (described below) or ‘Jenkins Mill #2’ pictured below.

On Harold Parker Road near the one-lane bridge lies the remains of a stone dam, likely used as a sawmill. The property was in the Jenkins/Butterfield family until being sold to the State.

The remains of Jenkins Mill #2 can still be seen from the road.

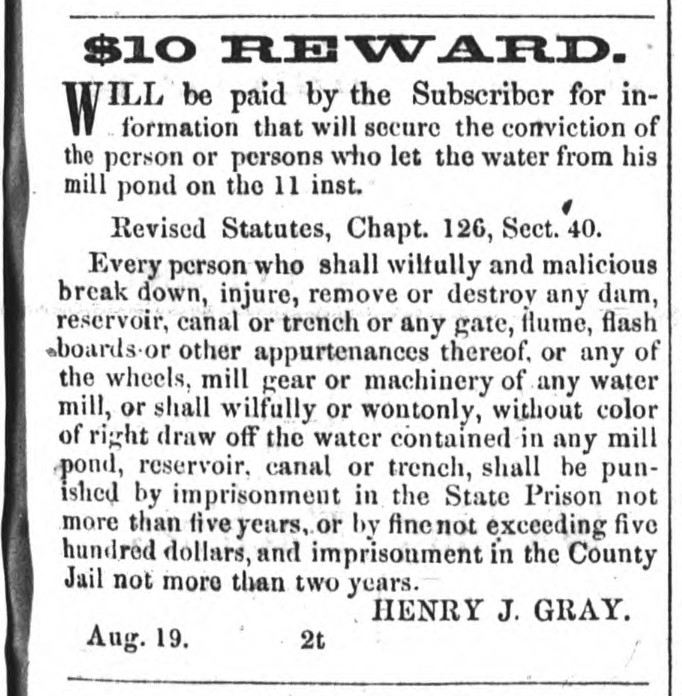

Gray’s Sawmill

Henry Jenkins Gray purchased a sawmill from Ebenezer Jenkins in 1853 for Four-hundred and twenty dollars, with the privilege of ‘repairing the upper dam’ using stone and gravel from Jenkins property. The deed specifies that Gray has the right to run the sawmill only from October 20th to April 20th each year.71 Local history has it that the mill was built by Ebenezer Jenkins father Samuel sometime before 1837 and left to Ebenezer in his will.72

In 1920, the Andover Natural History Society visited the newly created State Forest. An account of their trip appeared in the local newspaper where they describe “Gray’s saw mill” on “Old Mill Road”. They tell us that the mill was in operation until 1898 and the only remains at the time were “a few huge timbers and a fragment of the mill wheel..”73

In 1934, the Civilian Conservation Corps workers encountered the remains of Gray’s mill while constructing the Brackett Pond Dam. They describe digging up “numerous planks and timbers” and uncovering the wall of stone that made up the “rural old dam” to make way for the new concrete dam.74There are some fieldstone retaining walls still standing along this portion of Harold Parker Road that may be from the original dam, however, the CCC also used fieldstone construction making it difficult to differentiate the two.

Sawmill Road

At a town meeting in December of 1850, the section of Harold Parker Road that runs through the Western side of the park from Route 125 to Jenkins Rd. was officially named “Sawmill Road”.75Later shortened to ‘Mill Road’, the name continued to appear on maps until at least 1951.

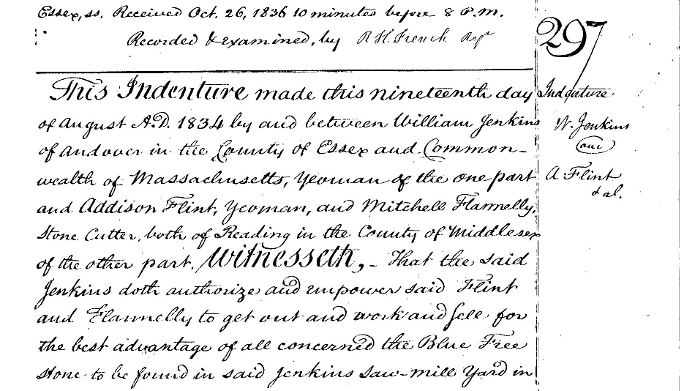

Jenkins Quarry

In 1834, William Jenkins (1796-1878) signed an agreement with Addison Flint and Mitchell Flanelley (both from Reading) to work the “Blue Free Stone to be found in said Jenkins Saw-Mill Yard”. This marked the beginnings of Jenkins Soapstone quarry which is shown on the State Trail Map. Remnants of the quarry can be seen near the trail including tool marks from quarrying activities. Addison and Flannelly were to be paid $2.50 for each day they worked plus ten-percent of the quarry profits.

1834 Contract between William Jenkins, Addison Flint and Mitchell Flannelly to work the Jenkins Quarry.

Underground Railroad

William Jenkins and his wife Polly Saltmarsh Jenkins were said to be “ardent abolitionists”. According to historian Kate Noyes, he represented Andover at the North Reading Freeman’s Convention which was organized to repeal the Fugitive Slave Act. They both left the South Parish Church over controversy related to the slavery issue and joined the Free Christian Church.

The Jenkins Farm (8 Douglass Ln) was known to be a site on the Underground Railroad. On February 28th, 1850 William Jenkins sent a letter to Wendell Phillips in Boston describing his concerns for a fugitive slave he was sheltering:

“a man came to me & brought a letter from you asking me to find him work or keep him otherwise, he stayed a few days and grew verry uneasy in a place like mine where every one is looking & inquiring who is that, wonder if he is a slave and it is a fact that anything will spread faster then it would in Boston and he being winter I could not keep him out of sight he was fearfull when 2 or 3 men called to speak with me he asked me what he had better do if he had ben to Canada & could not stay there I advised him to stear towards Cape Ann might be he could get a chance to go to the British W. I. Islands I did not dare send him to Boston I had none to advize with on the matter.” 76

While his sources have lately been criticized, Wibur H. Siebert received letters from Marion LaMere describing the Jenkins Farm as “the principal Underground station of the countryside, and is said to have been in operation from the 1830’s onward… Anti-slavery speakers were often guests in his house and Harriet Beecher Stowe was a frequent caller.” She mentions William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglas as visitors to the farm with George W. Latimer as one of the fugitives passing through77.

LaMere relates a story from William Jenkins’ daughter Elizabeth Butterfield who says that fugitive George Latimer stayed at the house, and while there he stood her on a table to “Illustrate how a slave girl was sold” and later sent her a doll as a gift78.

A recent history of the Andover South Church during the time of the abolition movement suggests that fugitives hid by posing as workers at the Jenkins sawmill. No source of the information is given.

“He ran a series of mills and when they suspected being detected, the runaway slaves took up positions working the mill.”79

The house itself contains a hollow space next to the chimney that was believed to be a hiding place.

Waste Lands

By the early 1900s the forest had been decimated by accelerated logging, forest fires and invasive species. The 1916 Boston Daily Globe article that announced the creation of the new State Forest describes the land purchased by the state as ‘waste land’. 80 The stated goal of the commission that created Harold Parker State Forest was to purchase ‘wild and waste lands’ to convert into state forests. 81

Many mark the beginning of the Industrial Revolution with the invention of James Watt’s steam engine in the late 1700s. 82 Watt’s engine had various applications including the steam sawmill which was patented in 1798. 83 While slow to come into use, it made its way to the South Andover woods sometime before 1867. John B. Jenkins, the nephew of William Jenkins, had a farm just north of the present day park boundary near his Uncle. 84 In 1867 the local paper reported that his steam sawmill was destroyed in a wind storm. 85 By 1872, the same paper reports that his steam mill had been rebuilt and was running again. 86

The earlier water-powered mills of Jenkins and Gray were run seasonally in the winter and early spring to avoid interfering with other agricultural activities. They operated at the whims of water current and had comparatively low output. 87 The new steam mills could be run year round. Many were ‘portable’ and could be operated a distance from any water supply. Various other improvements increased the efficiency and output of these machines throughout the late 1800s and early 1900s. 88

At the same time that improvements were being made to sawmill technology, the industries of nearby Lawrence and Lowell were increasing the demand for lumber. The forests were no longer managed as small family-owned businesses, they became part of a much larger industrial supply chain. In 1880, one of William Jenkins’ surviving daughters sold the lumber on 70 acres of his estate to a box company. 89 In 1888, an editorial decrying the cutting of the forests was published in the local paper describing three separate large-scale steam mills operating in the confines of what is now Harold Parker State Forest. 90

Forest fires were rampant in the late 1800s. In at least one instance, the sparks from the engine of a steam mill were to blame for a 100 acre fire at the William Jenkins estate. Ironically, this was the same fire that destroyed the original wooden Jenkins’ sawmill building in 1893. 91 The Boston Daily Globe describes an enormous fire in 1896 that covered several square miles spanning the entire Andover, North Reading town line from Wilmington to Middleton. 92

In the late 1860s a French naturalist named Leopold Trouvelot was experimenting with imported European Gypsy Moths at his home in Medford, Massachusetts. A number of the moths escaped, bred in the wild and began to defoliate and kill trees in the area. 93 By 1905 the moths had spread to North Andover, arriving in Andover shortly afterwards. 94,95,96 The forest trees which had not already been cut or burned were subject to defoliation and possibly death with the arrival of this new pest.

Conservation Movement

The scene at Andover was not uncommon during the 1800s. Throughout most of the century there were few laws in place to prevent forest fires, little understanding of invasive species and no public or private entities with the authority and resources to preserve the land. In 1620 it’s estimated that 90% of Massachusetts was covered with forest, by 1850 only 30% was forested. A number of factors came together to awaken the conservation movement in the second half of the 1800s.

Starting mid-century, writers such as Henry David Thoreau and George Perkins Marsh were lamenting the overexploitation and loss of the natural landscape. Artists associated with the Hudson River School inspired the public with romantic paintings of natural scenes. The influence of labor unions offered greater leisure time to industrial workers who engaged in more outdoor recreation and desired spaces nearer to urban areas to do so. These and other factors were the basis for the early popular environmentalist movement rooted in aesthetics, spirituality and public health.

White pine had long been the primary building material in the country. Following the Civil War, high-demand combined with the exhaustion of local supplies began to drive up prices in Massachusetts and the rest of New England. At one time, New England provided the majority of wood for construction and fuel from its own forests but now timber was being imported from the Southern and Western states in large quantities. Around these concerns rose a conservationist movement based in utilitarian and economic motives.

These two sets of motives were not mutually exclusive. Proponents of conservation and preservation argued both perspectives.

Organizations concerned with preservation, conservation and recreation began to form in the late 1800s. One of the earliest in Massachusetts was the Appalachian Mountain Club in 1876. The first land trust in the country, the Trustees of Reservations (formerly the Trustees of Public Reservations) formed in 1891. Massachusetts Audubon formed in 1896 and the Environmental League of Massachusetts (formerly the Massachusetts Forestry Association) formed in 1898.

The officers of these organizations were often well connected and influential in furthering state legislation to create public reservations and protect natural resources. In 1882 the legislature passed a law allowing individual towns and cities to create municipal forests, leading to the creation of Lynn Woods in 1888 and Andover’s own Indian Ridge Reservation in 1897 along with a host of others.

In 1893 the state passed a law providing a loan to 37 cities and towns surrounding and including Boston to cooperatively create the Metropolitan Parks system including the Middlesex Fells Reservation and the Blue Hills Reservation.

Out of concerns that commercial activity would damage or destroy their natural beauty, the state provided funds to purchase several state reservations including Mount Greylock Reservation, Mount Wachusett Reservation and the Mount Tom Reservation.

In 1904 the state created the office of State Forester. With the appointment of Frank William Rane as the second State Forester in 1906 and assistance from the Massachusetts Forestry Association (later ELM) a flurry of laws to protect and restore the state forests ensued culminating with the creation of the Massachusetts State Forest Commission in 1914.

Creation of the Park

In 1914, out of concerns surrounding lumber shortages and the purchase of foreign lumber, the State Legislature of Massachusetts created the State Forest Commission with the stated purpose of purchasing and reforesting ‘wild lands’ which had been stripped of trees. The commission was made up of Harold Parker, Harvey Shepard and Frank Rane with Parker as the chairman. By 1915 the commission had identified 800 acres of land in North Andover and Reading to establish a State Forest. The report of the commission comments that “This country is well adapted to the growth of white pine; it is, in short, a typical pine country, the standing trees showing unusual size and vigor.”97 On April 14th, 1916 thirteen deeds were filed at Essex County purchasing approximately five-hundred and fifty acres of land from ten families. The largest tracts were purchased from the families of Campbell, Upton, Gray (of Gray’s sawmill) and Butterfield (William Jenkins daughter)98. On November 29th, 1916 State Forest Commission Chairman, Harold Parker, passed away “after a brief illness”. The park was named in his honor.99

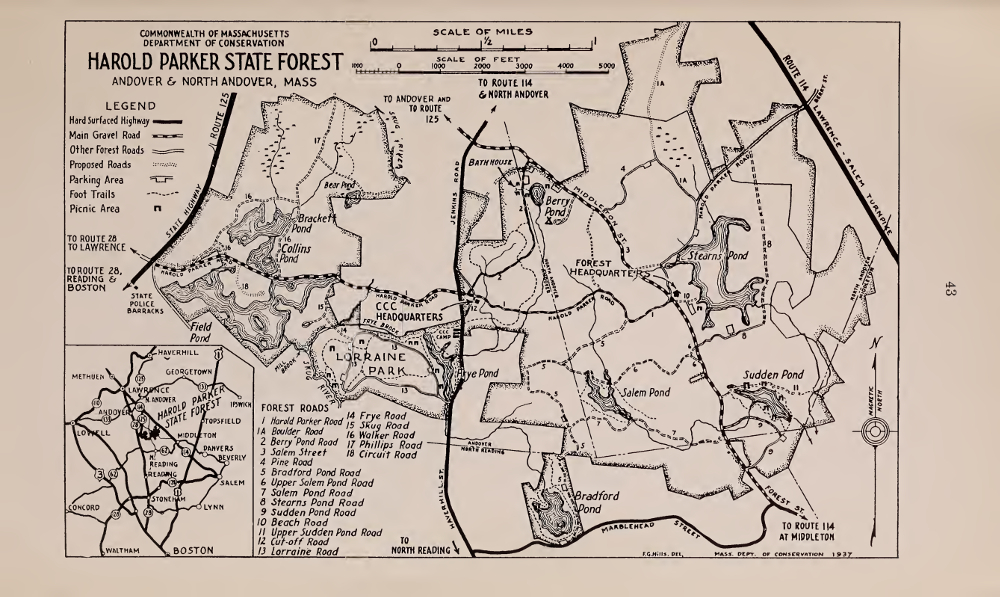

Between 1916 and the start of World War II, the State Forest Commission and later the Department of Conservation continued to acquire land and make improvements including road maintenance, pest control and reforestation. Hundreds of thousands of pine trees were planted, many of which can be observed today as almost pure stands of red and white pine.

Civilian Conservation Corps

In the fall of 1929, the economy of the United States collapsed. For the most vulnerable Americans, it was devastating. People of all ages and backgrounds found themselves without work or income, many becoming homeless. The initial government response was anemic and little was to change for the next several years.

In 1933, the unemployment rate was approaching 25% when newly elected Franklin D. Roosevelt began to enact a series of public works and relief agencies collectively known as the ‘New Deal’. The very first of these agencies to be created was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC).

The CCC was created with unprecedented speed. Roosevelt’s inauguration was held on March 4th, 1933. He sent the draft legislation creating to CCC to Congress on March 21st, 1933 and after much debate and negotiation, both houses of Congress passed the bill with bipartisan support and Roosevelt signed it into law on March 31st, 1933.

An advisory council appointed to implement the bill decreed only single men between the ages of 18 and 25 would be eligible. When possible, enrollees would be recruited from the welfare rolls of each state. A six-month commitment would be required, and they would be paid $30 per month, of which, $25 would be sent back to their families. Later in year it was agreed that veterans and Native Americans who did not meet these requirements could also enroll.

Each camp would be made up of approximately 200 men. Camp operations and logistics would be overseen by an Army commanding officer while conservation work would be directed by a camp superintendent with a forestry background. In order to ensure the safety of these young urban men with little outdoors experience, the camps were also staffed with several “local experienced men’ to supervise the day to day work.

On April 14th, 1933, two weeks after the C.C.C. was officially created, the first 87 Massachusetts men arrived by train at Fort Devens for physical examinations and training. Six weeks later, on May 30th, 1933, 190 men from cities and towns including Worcester, Chicopee, Springfield, Salem and Lynn arrived at the forest in Andover. Another 20 men were to arrive later. This was to be the 110th Company of the Civilian Conservation Corps.

The second CCC camp arrived at the forest on December 7th, 1933. The 167th Company of the Civilian Conservation Corps was transferred from Danby, Vermont to Harold Parker State Forest. These men, most of whom were native to Vermont, set up camp on the Northern end of Frye Pond just off Lorraine Road.

The CCC was assembled so quickly that no preparations were made for their arrival. The 110th company spent their first day at Harold Parker clearing space in the forest near what is now Brackett Pond in order to set up large tents and makeshift stoves for food preparation. While its beginnings were austere, one year later the 110th camp boasted of a recreation room with a large stone fireplace, four wooden barracks, a twenty-five table mess hall, an infirmary, lavatory, supply barracks, garage and a small gym. While no longer identifiable, the remains of some of these structures can be seen alongside the trails which skirt the southern edge of the pond.

Over the course of the next eight years the CCC would make extensive and lasting changes to Harold Parker and surrounding State Forests. While the 110th company would be transferred to Freetown, MA in 1935, the 167th company would continue operating at Harold Parker until 1941, becoming one of the last remaining CCC camps in Massachusetts.

Most of the work done by the CCC in Massachusetts fell under the auspices of forestry. The enrolled men created fire roads, planted and thinned tree stands to encourage the growth of marketable timber and removed gypsy moths and brown-tail moths from the forest. This work was also done at Harold Parker but the forest was designated as a recreational area almost immediately following the arrival of the CCC. The work to be done here would be more labor intensive and far-reaching.

One of the first projects completed by the 110th company in 1933 were the pair of eight foot tall stone pillars adorning the entrance to the park from Route 125. They also extended Harold Parker Road (formerly Mill Street) from Route 125 to reach Jenkins Road, built the small bridge which spans the Skug River and constructed numerous trails and fire roads. The 167th company laid out the Lorraine Park Campground, built the Park Headquarters and facilities buildings on Salem Street, constructed the Berry Pond Beach and picnic pavilion along with numerous other bathhouses, fireplaces and retaining walls throughout the park.

The largest and most transformative project for both companies was the construction of the nine man-made ponds spread across the forest. The four Western ponds, Field, Collins, Brackett and Delano were the work of the 110th company. Originally designated by simple numbers (ponds one through four), the ponds were renamed in 1936 for four former Massachusetts Commissioners of Fish and Game (Charles Field, Joseph Collins, Edward Brackett, and John Delano). At the time that the 110th company was moved to Freetown (1935), the first three dams had been completed and work on the dam for Delano pond was suspended. It was determined in the same year that the Field Pond dam was leaking. It was pdrained for repair with work on both Field and Delano completed in 1936. The Eastern ponds, Stearns, Salem, Sudden, Frye and Bradford were all c;ompleted by 1935. In addition to being recreational areas, all of the ponds served to varying degrees as fish hatcheries for the Massachusetts Department of Fish and Game up until 1983. Numerous species were bred and raised here for use in stocking other local lakes and ponds. A now partially submerged Fish Sorting House built in 1940 can be seen alongside Harold Parker Road at the Southern end of Collins Pond.

WWII and Later

Throughout the history of the park, Harold Parker has been used as a source of fuel-wood and commercial timber. During the 1940s and again in the 1970s, programs were established to allow local homeowners to cut cord wood in the park. Most recently, the State has harvested commercial timber starting in the 1980s and continuing through 2010. Most of the eastern half of Harold Parker is classified as a “Woodland” under the state’s Landscape Designation Guidelines. This means that the land is primarily managed for forestry. The western half (west of Jenkins road) is designated as “Parkland” and is managed for recreational purposes.

Geology

Geologists map and name ‘Geological Units’ which indicate bedrock that formed in similar ways, usually at the same time. Harold Parker has four such units; Andover Granite, Sharpners Pond Diorite, Shawsheen Gneiss and the Nashoba Formation.

Shawsheen Gneiss is a metamorphic rock, medium-gray, with irregularly sized but generally medium grained crystals, unevenly layered white and black mica-quartz-feldspar gneisses.

Andover Granite is an igneous rock, light, commonly pink with muscovite and garnet. The slightly younger Andover granite formed between 450 to 412 million years ago. The Andover granite formed from the melting of deeply buried sedimentary rock and intrudes (cuts through) the older Gneiss.

Sharpners Pond Diorite is a dark igneous rock composed mainly of biotite mica and black hornblende. Sharpners Pond diorite intruded

the older Andover granite formations about 430 million years ago.

The Nashoba formation is a complex formation made up of layers of schist and gneiss and amphibolite. Amphibolite is the most abundant component in the park.

There is heavy evidence of the Wisconsinan Glaciation throughout Harold Parker. The soils were scraped bare by the glacier and a thin layer of glacial till covers most areas. Woodchuck hill is a glacial drumlin, Bear and Berry Ponds are kettle ponds, there are areas of glacial outwash on the Northeast shore of Stearns Pond and portions of the western shore of Salem Pond. Glacial erratics are strewn throughout Harold Parker, the largest of which can be seen on the Bay Circuit Trail just west of Jenkins Road near trail marker A9.

Plants and Vegetation

Much, if not all of the forest at Harold Parker was at one time pasture or agricultural land. The stone walls which lined the edges of the fields now run through dense forest. When the farmland and pasture was abandoned in the 1800s, a second growth forest was allowed to grow. During the late 1800s and early 1900s this second-growth forest was heavily harvested for timber and was subject to frequent forest fires, potentially caused by the nearby railroad. Upon the creation of the park, enormous pure stands of White and Red Pine were planted to reforest the area. All of these factors contribute to and shape the current composition of Harold Parker’s plants and vegetation.

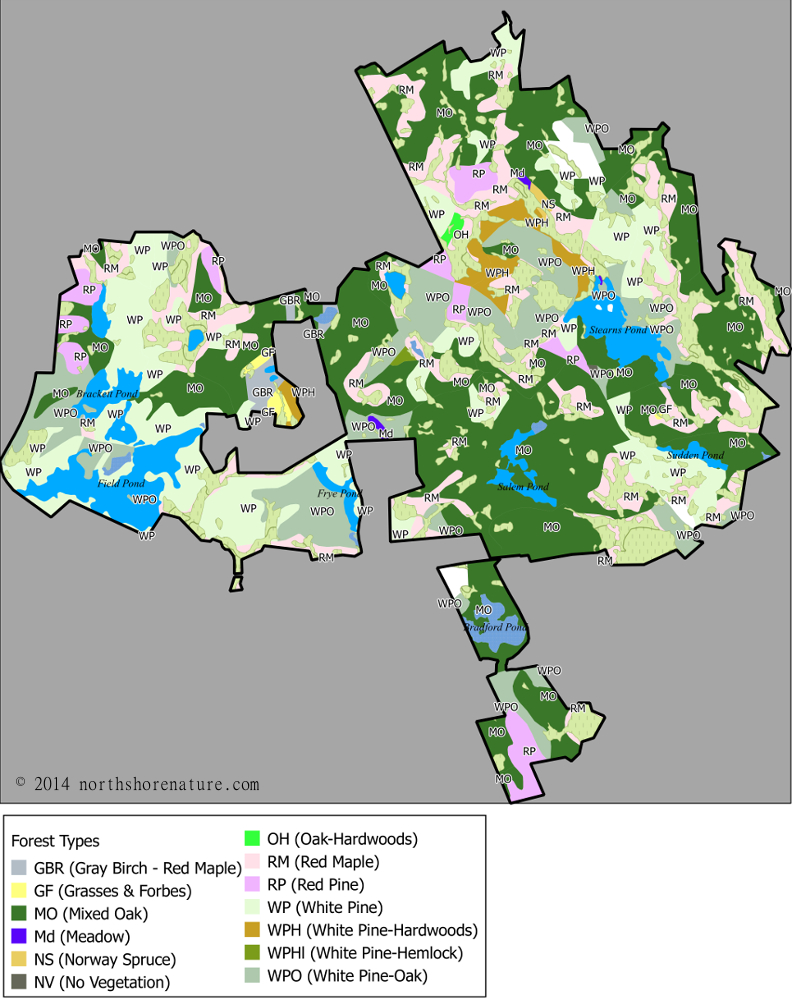

As seen in the map above, most of the park is covered by Mixed Oak and White Pine forests with Red Maple swamps occurring in the low wetland areas.

Sources:

1 Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (2013) Harold Parker planning unit, including Harold Parker State Forest and Boxford State Forest : resource management plan

2 Bullen, Ripley P. (1949) Excavations In Northeastern Massachusetts p.61

3 Wall, Suzanne (2003) “Aboriginal Soapstone Workshops at the Skug River II Site, Essex County, MA” Bulletin Of The Massachusetts Archaeological Society, Volume 64 (2), Fall 2003

4 Lizee, Jonathan Michael, “Prehistoric ceramic sequences and patterning in southern New England: The Windsor Tradition” (1994).

5 Petzold, Arthur (1961) “The Eaton Site: A Dugout Workshop” Bulletin Of The Massachusetts Archaeological Society, Volume 22 April-July, 1961 NOS. 3 and 4

6 Bullen, Ripley P. (1949) Excavations In Northeastern Massachusetts p.61

7 Palter, John L. (1976) A New Approach to the Significance of the “Weighted” Spear Thrower. American Antiquity 41(4):500-509.

8 Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (2013) Harold Parker planning unit, including Harold Parker State Forest and Boxford State Forest : resource management plan

9 Bright, W. (2004). Native American placenames of the United States. Norman: University of Oklahoma.(snake river)

10 Douglas-Lithgow, R. A. (1909). Dictionary of American-Indian place and proper names in New England: With many interpretations, etc. m, Mass.: Salem Press.(black river)

11 The Andover Townsman (12/3/1920) p.8 “Siftings”

12 Lepionka, Mary Ellen (2014) “Who Were the Agawam Indians Really?” (https://storiesfromipswich.org/ Retrieved 1/25/2017)

13 Perley, S. (1912). The Indian land titles of Essex County, Massachusetts

14 Snow, D. (1980). The archaeology of new england (New world archaeological record). New York: Academic Press.

15 Snow, D. (1980). The archaeology of new england (New world archaeological record). New York: Academic Press.

16 1855 Chap. 0150. An Act To Divide The Town Of Andover, And To Incorporate The Town Of North Andover.

17 Wheatland, H. (1878). Standard history of Essex County, Massachusetts: Embracing a history of the County from its 1. Settlement to the present time, with a history and description of its towns and cities.

18 Greven, P. J. (1970). Four generations: Population, land, and family in colonial Andover, Massachusetts.

19 Greven, P. J. (1970). Four generations: Population, land, and family in colonial Andover, Massachusetts.

20 Greven, P. J. (1970). Family structure in seventeenth-century Andover, Massachusetts.

21 Essex County, MA: Probate File Papers, 1638-1881. New England Historic Genealogical Society. Osgood, John. Case # 20215

22 Southern District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds, Book 85, Page 305 (Peter Osgood to Samuel Jenkins) (6/12/1745)

23 Greven, P. J. (1970). Four generations: Population, land, and family in colonial Andover, Massachusetts.

24 Essex County, MA: Probate File Papers, 1638-1881. New England Historic Genealogical Society. Osgood, John. Case # 20215

25 Andover (Mass.) Town Records 1656-1709

26 Andover (Mass.) Town Records 1656-1709

27 Osgood, Ira; Putnam, Eben (1894) “A genealogy of the descendants of John, Christopher and William Osgood, who came from England and settld in New England early in the seventeenth century” (pgs. 9,10,11 & 15)

28 Essex County, MA: Probate File Papers, 1638-1881. New England Historic Genealogical Society. Osgood, John. Case # 20215

29 Osgood, Ira; Putnam, Eben (1894) “A genealogy of the descendants of John, Christopher and William Osgood, who came from England and settld in New England early in the seventeenth century” (pgs. 9,10,11 & 15)

30 Southern District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds, Book 26, Page 151 (John Osgood to Peter Osgood)

31 Southern District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds, Book 26, Page 153 (Samuel Osgood to Peter Osgood)

32 Southern District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds, Book 85, Page 305 (Peter Osgood to Samuel Jenkins) (6/12/1745)

33 Southern District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds, Book 100, Page 140 & 141 (two deeds) (Martha Osgood to Jabez Hayward) (4/27/1754) (5/10/1754)

34 Southern District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds, Book 106, Page 156 (Martha Osgood to Joshua Upton) (Note: this was later sold to Hayward and described as part of Osgood’s Farm) (4/10/1754)

35 Southern District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds, Book 126, Page 202 (Peter Cheever and wife to Samuel Jenkins Jr.) (6/17/1769)

36 Southern District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds, Book 129, Page 249 (Jabez Hayward et. al. to Dudley Woodbridge) (1/21/1772)

37 Southern District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds, Book 129, Page 250 (Dudley Woodbridge et. al. to Samuel Jenkins Jr.) (1/21/1772)

38 Southern District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds, Book 129, Page 251 (Dudley Woodbridge et. al. to Samuel Woodbridge) (1/21/1772)

39 Southern District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds, Book 131, Page 195 (Dudley Woodbridge to Ezra Putnam) (4/6/1773)

40 Essex County, MA: Probate File Papers, 1638-1881. New England Historic Genealogical Society. Osgood, Peter. Case # 20254

41 Southern District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds, Book 26, Page 153 (Samuel Osgood to Peter Osgood)

42 Oxford Online Dictionary (https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/gibbet) Retrieved 1/14/2017

43 Hearn, Daniel Allen (1999) Legal Executions in New England: A Comprehensive Reference, 1623-1960 (pg. 60)

44 Mooar, George (1859) “Historical Manual of the South Church in Andover” (pg. 19)

45 Massachusetts Acts, 1904. — Chaps. 251, 252. (pgs. 213 – 214)

46 North District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds Plan # 2906

47 Southern District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds, Book 56, Page 207 (Gray to Gray) “John Carlton’s Path”

48 Southern District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds, Book 41, Page 277 (Carlton to Gray) John Carlton Cooper

49 Southern District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds, Book 89, Page 12 (Gray to Gray) Abraham Foster carting hay.

50 Southern District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds, Book 281, Page 243 (Blunt to Gray) Falls Woods & Carlton Path

51 North District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds (Bk. 363 Pg. 150 , Bk. 363 Pg. 159 , Bk. 373 Pg. 444 , Bk. 383 Pg. 415 , Bk. 383 Pg. 418 , Bk. 426 Pg. 23 , Bk. 520 Pg. 136 , Bk. 552 Pg. 537 , Bk. 582 Pg. 482 , Bk. 590 Pg. 387 , Bk. 591 Pg. 597 , Bk. 597 Pg. 227 , Bk. 604 Pg. 580) Comm. of Mass – “Falls Woods” deeds

52 Southern District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds (Bk 14 Pg. 73 ,Bk 32 Pg. 130 ,Bk 56 Pg. 207 ,Bk 89 Pg. 12 ,Bk 108 Pg. 200 ,Bk 110 Pg. 158 ,Bk 112 Pg. 249 ,Bk 115 Pg. 120 ,Bk 121 Pg. 72 ,Bk 121 Pg. 74 ,Bk 122 Pg. 77 ,Bk 123 Pg. 222 ,Bk 128 Pg. 76 ,Bk 131 Pg. 195 ,Bk 150 Pg. 50 ,Bk 154 Pg. 258 ,Bk 155 Pg. 21 ,Bk 159 Pg. 69 ,Bk 163 Pg. 209 ,Bk 176 Pg. 153 ,Bk 189 Pg. 44 ,Bk 216 Pg. 285 ,Bk 245 Pg. 228 ,Bk 281 Pg. 243 ,Bk 310 Pg. 79 ,Bk 472 Pg. 75 ,Bk 517 Pg. 210 ,Bk 527 Pg. 49 ,Bk 579 Pg. 166 ,Bk 872 Pg. 112 ,Bk 69 Pg. 81 ,Bk 139 Pg. 98 ,Bk 207 Pg. 581) Historical – “Falls Woods” deeds

53 The Andover Townsman 9/3/1915 p.3 “HISTORICAL ANDOVER No. 161 Some Old Landmarks”

54 Andover Massachusetts Town Meeting Records (1656-1709) (pg. 0371 – 01/04/1685)

55 Southern District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds, Book 233, Page 164 (Cummings to Hayward) and Book 361, Page 114 (Hayward to Gray) (Note: These Deeds and the following reference establish that the present day ‘Bear Pond’ was historically referred to as ‘Bare Meadow Pond’)

56 Northern District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds, Book 315, Page 216 (Gray to Batchelder) and Book 373, Page 444 (Batchelder to Commonwealth of Massachusetts) (Note: These Deeds and the previous references establish that the present day ‘Bear Pond’ was historically referred to as ‘Bare Meadow Pond’)

57 Southern District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds, Book 107, Page 239 (John Holt to John Holt 3rd) (Note: This deed places the Holt Saw Mill adjacent to ‘Bare Meadow’ which is the historical name of present day ‘Bear Pond’)

58 Essex County, MA: Probate File Papers, 1638-1881. New England Historic Genealogical Society. Osgood, John. Case # 20215

59 Southern District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds, Book 246, Page 75 (Eben Jones to William Jenkins); Southern District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds, Book 204, Page 190 (William Holt to Jacob Jones); Southern District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds, Book 722, Page 276 (Samuel Abbott to William Jenkins);

60 Andover Townsman 5/26/1893 p.1 (Original Sawmill Burned)

61 Southern District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds, Book 194, Page 77 (Benjamin Upton to Benjamin Jenkins)

62 Southern District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds, Book 114, Page 80 (Nathaniel Holt to Samuel Jenkins)

63 Southern District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds, Book 171, Page 147 (Tim Fuller to Benj. Upton Esq.)

64 Southern District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds, Book 194, Page 77 (Benjamin Upton to Benjamin Jenkins)

65 Southern District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds, Book 346, Page 67 (B. Jenkins to Wm. Jenkins)

66 Fuller, William Hyslop, 1919 ‘Genealogy of some descendants of Thomas Fuller of Woburn’

67 Hurd, D Hamilton, 1888 ,History of Essex County Massachusetts with Biographical Sketches of Many of Its Pioneers and Prominent Men (Pg.949)

68 Siebert, Wibur H. (1935) “The Underground Railroad In Massachusetts”

69 National Park Service “The Underground Railroad in Massachusetts, 1783-1865 MPS”

70 Goldsmith, Bessie P. (1964) “The Townswoman’s Andover” pgs. 20 – 22 ‘William Jenkins House’

71 Southern Essex District Registry of Deeds (Book 482, Pg. 15 Jenkins to Gray)

72 The Andover Townsman (Friday, December 3, 1920 – pg. 8)

73 The Andover Townsman (Friday, December 3, 1920 – pg. 8)

74 Harold Parker Review (Civilian Conservation Corps Newsletter) 11/29/1934

75 Northern Essex District Registry of Deeds (Book 383, Pg. 419 Gray to Commonwealth of Massachusetts)

76 National Park Service “The Underground Railroad in Massachusetts, 1783-1865 MPS”

77 Siebert, Wibur H. (1935) “The Underground Railroad In Massachusetts”

78 Siebert, Wibur H. (1935) “The Underground Railroad In Massachusetts”

79 Lyons, Charlotte (2011) South Church: Founding History and Abolitionism: An Essay Regarding New Facts

80 Boston Daily Globe 8/17/1916 p.6 “Land for New Forest”

81 Report of The Massachusetts State Forest Commission (1914) p.7 (Waste Land)

82 The International Steam Engineer, Volume 25 (Watt Steam Patents)

83 Bishop, J. Leander (1864) “A History Of American Manufactures From 1608 to 1860” (Steam Sawmill Patents)

84 North District Essex County Massachusetts Registry of Deeds Land Plan # 433

85 Andover Advertiser 12/6/1867 p.2 (Jenkins Steam Mill destroyed)

86 Lawrence American 2/9/1872 p.2 (Symonds injured at Jenkins Steam Mill)

87 Martha Blanchard Lance, “`The fathers lived in the forests: Their children live off them’; rural New England sawmilling and the timber trade, 1730–1870” (January 1, 1993). Chapter 2 pgs. 57-148

88 Bishop, J. Leander (1864) “A History Of American Manufactures From 1608 to 1860” (Steam Sawmill Patents)

89 Lawrence American December 3rd, 1880 p. 2 (Timber sold to Box Company)

90 The Andover Townsman 3/16/1888 p.2 “The Cutting down of Andover Timber”

91 Andover Townsman 5/26/1893 p.1 (Original Sawmill Burned)

92 Boston Daily Globe (5/19/1896) p.1 “Acres Ablaze”

93 Furbush, Edward H. and Fernald, Charles H. (1896) “The Gypsy Moth”

94 ANNUAL MEETING Board of Agriculture BOSTON. January 10 and 11, 1905.

95 Second Annual Report Of The Superintendent For Suppressing the Gypsy and Brown-tail Moths. (January 1907) pgs.27, 59, 86 – 87

96 Third Annual Report Of The Superintendent For Suppressing the Gypsy and Brown-tail Moths. (January 1908) pgs. 62-63, 103

97 Annual Reports of the Massachusetts State Forest Commission (1914 – 1919)

98 Northern Essex District Registry of Deeds (Book 363, Pgs. 141,143,145,146,148,149,150,154,159,160,162,163,165)

99 Annual Reports of the Massachusetts State Forest Commission (1914 – 1919)